WQI’s Jen Choy was featured in an AZoQuantum feature for International Day of Women and Girls in Science. Read the piece here.

Quantum Sensing

Opening doors to quantum research experiences with the Open Quantum Initiative

This past winter, Katie Harrison, then a junior physics major at UW–Madison, started thinking about which areas of physics she was interested in studying more in-depth. “Physics is in general so broad, saying you want …

Read the full article at: https://www.physics.wisc.edu/2022/08/29/opening-doors-to-quantum-research-experiences-with-the-open-quantum-initiative/Coherent light production found in very low optical density atomic clouds

No atom is an island, and scientists have known for decades that groups of atoms form communities that “talk” to each other. But there is still much to learn about how atoms — particularly energetically …

Read the full article at: https://www.physics.wisc.edu/2022/07/21/coherent-light-production-found-in-very-low-optical-density-atomic-clouds/Ultraprecise atomic clock poised for new physics discoveries

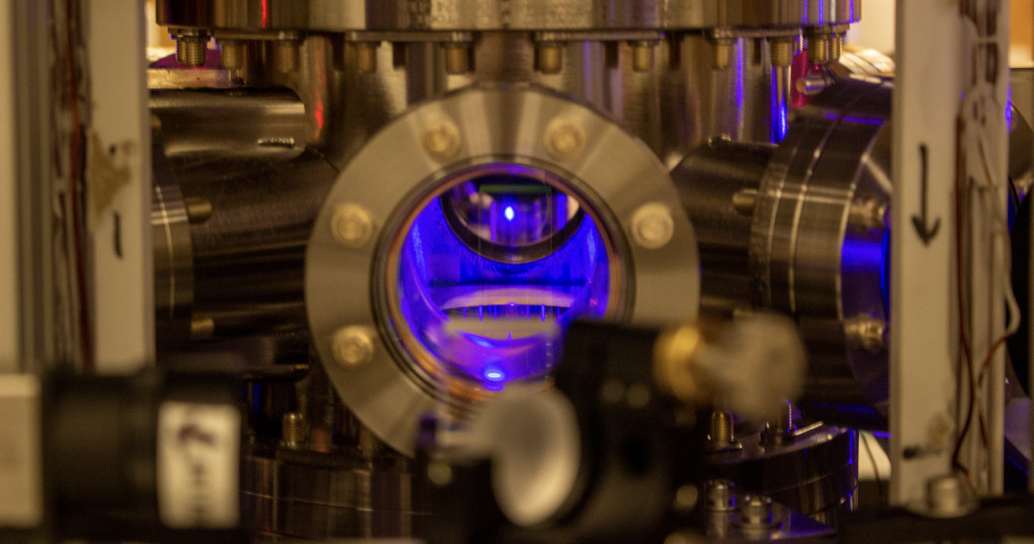

Wisconsin Quantum Institute physicists have made one of the highest performance atomic clocks ever, they announced Feb. 16 in the journal Nature.

Their instrument, known as an optical lattice atomic clock, can measure differences in time to a precision equivalent to losing just one second every 300 billion years and is the first example of a “multiplexed” optical clock, where six separate clocks can exist in the same environment. Its design allows the team to test ways to search for gravitational waves, attempt to detect dark matter, and discover new physics with clocks.

“Optical lattice clocks are already the best clocks in the world, and here we get this level of performance that no one has seen before,” says Shimon Kolkowitz, a UW–Madison physics professor with WQI and senior author of the study. “We’re working to both improve their performance and to develop emerging applications that are enabled by this improved performance.”

Atomic clocks are so precise because they take advantage of a fundamental property of atoms: when an electron changes energy levels, it absorbs or emits light with a frequency that is identical for all atoms of a particular element. Optical atomic clocks keep time by using a laser that is tuned to precisely match this frequency, and they require some of the world’s most sophisticated lasers to keep accurate time.

By comparison, Kolkowitz’s group has “a relatively lousy laser,” he says, so they knew that any clock they built would not be the most accurate or precise on its own. But they also knew that many downstream applications of optical clocks will require portable, commercially available lasers like theirs. Designing a clock that could use average lasers would be a boon.

Shimon Kolkowitz awarded Sloan Fellowship

Four University of Wisconsin–Madison professors, including WQI’s Shimon Kolkowitz, have been named to Sloan Research Fellowships — competitive, prestigious awards given to promising researchers in the early stages of their careers.

“Today’s Sloan Research Fellows represent the scientific leaders of tomorrow,” says Adam F. Falk, president of the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, which has awarded the fellowships since 1955. “As formidable young scholars, they are already shaping the research agenda within their respective fields—and their trailblazing won’t end here.”

Kolkowitz, an assistant professor of physics, builds some of the most precise clocks in the world by trapping ultracold atoms of strontium — clocks so accurate they could be used to test fundamental theories of physics and search for dark matter.

UW–Madison’s other 2022 Sloan Fellows are Tatyana Shcherbina (math), Zachary K. Wickens (chemistry) and Andrew Zimmer (math).

The UW–Madison professors are among 118 researchers from the United States and Canada honored by the New York-based philanthropic foundation. The four new fellows join 110 UW–Madison researchers honored in the past.

Each fellow receives $75,000 in research funding from the foundation, which awards Sloan Research Fellowships in eight scientific and technical fields: chemistry, computer science, economics, mathematics, computational and evolutionary molecular biology, neuroscience, ocean sciences and physics.

Shimon Kolkowitz earns NSF CAREER award

Shimon Kolkowitz has already developed one of the most precise atomic clocks ever. Now, the UW–Madison physics professor has been awarded a Faculty Early Career Development (CAREER) award from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to …

Read the full article at: https://www.physics.wisc.edu/2021/12/15/shimon-kolkowitz-awarded-nsf-career-award/Chicago Quantum Exchange Profile: Jennifer Choy

WQI’s Jennifer Choy was recently featured as part of a series of profiles of scientists and engineers from across the Chicago Quantum Exchange member institutions. This post was originally published by CQE.

Jennifer Choy is an assistant professor of engineering physics at the University of Wisconsin–Madison who studies quantum sensing and nanophotonics. She aspires to be a great mentor to undergraduate and graduate students and encourages students to study quantum science, even if they don’t plan to go into the field.

Tell us about what you’re working on now.

We are developing miniaturized and mobile quantum sensors and engineering quantum platforms to improve their sensing performance. We are interested in two material platforms in particular: neutral atoms and solid-state color centers. Our group is applying techniques in nanoscale optics and integrated photonics to exert precise control over atom-photon interactions and miniaturize atomic sensors. We are currently developing chip-scale, near-infrared polarization optics for alkali vapor magnetometers, which could enable compact, sensitive magnetic-field-imaging devices.

How does UW–Madison help advance your work?

UW-Madison has a strong research community in quantum computing and sensing platforms and is supported by groups across many science and engineering departments. It has been very inspiring and exciting to establish relationships and collaborations with top-notch quantum researchers at UW-Madison and in the Midwest under the Wisconsin Quantum Institute and the Chicago Quantum Exchange.

How did you become interested in quantum research?

As a freshman in the Nuclear Science and Engineering department at MIT, I joined David Cory’s group, working on using liquid-state nuclear magnetic resonance as a testbed for quantum computing. I think how someone gravitates toward a field depends greatly on formative experiences and environments. I had no prior knowledge in quantum physics, but graduate students in the group were very supportive and David always graciously answered questions and offered advice, even long after I graduated. I aspire to being able to foster a similar mentoring approach and attitude.

What does the future hold for quantum technology?

The use of quantum science in sensors and sensing brings a set of tools that can promise greater sensitivity and accuracy than conventional technologies, some of which are already in use. However, to make the next leap to other practical applications outside of the lab, a combination of fundamental science research and engineering will be needed to realize functional and robust sensor systems. Broader applications would include quantum accelerometers, gyroscopes, and clocks that can provide accurate navigation solutions without the need for GPS.

Quantum technology has a workforce shortage. What would you say to a young person who is interested in studying quantum information science?

I think part of the excitement of working in the field of quantum information science is that it offers interesting research directions in almost every science and engineering discipline. Developing quantum technologies requires partnership among academia, national labs, and industry. With several federally funded quantum initiatives, job opportunities will likely open up in all these sectors.

As someone who worked in industry (as a scientist at Draper Laboratory), what I really appreciated about my training in quantum research is that I was able to apply my skills to other unrelated fields, which were just as interesting and fulfilling. Therefore, I think a quantum workforce will generate well-rounded talents that will also benefit other industries.

MSPQC student Jacques Van Damme publishes first-author paper with WQI faculty

Congrats to Jacques Van Damme, a member of the first class of MSPQC students who graduated this past August, on his first-author publication! The study, published in Physical Review A, is titled, “Impacts of random filling on spin squeezing via Rydberg dressing in optical clocks.” Co-authors include WQI faculty members Mark Saffman, Maxim Vavilov, and senior author Shimon Kolkowitz. | Link to the PRA publication

Shimon Kolkowitz awarded two grants to push optical atomic clocks past the standard quantum limit

Optical atomic clocks are already the gold standard for precision timekeeping, keeping time so accurately that they would only lose one second every 14 billion years. Still, they could be made to be even more precise if they could be pushed past the current limits imposed on them by quantum mechanics.

With two new grants from the U.S. Army Research Office, an element of the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command’s Army Research Laboratory, UW–Madison physics professor Shimon Kolkowitz proposes to introduce quantum entanglement — where atoms interact with each other even when physically distant — to optical atomic clocks. The improved clocks would allow researchers to ask questions about fundamental physics, and they have applications in improving quantum computing and GPS.

WQI researchers awarded DOE Quantum Information Science grant

Three UW–Madison physics professors and their colleagues have been awarded a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) High Energy Physics Quantum Information Science award for an interdisciplinary collaboration between theoretical and experimental physicists and experts on quantum algorithms.

The grant, entitled “Detection of dark matter and neutrinos enhanced through quantum information,” will bring a total of $2.3 million directly to UW-Madison. Physics faculty include principal investigator Baha Balantekin as well as Mark Saffman, and Sue Coppersmith. Collaborators on the grant include Kim Palladino at the University of Oxford, Peter Love at Tufts University, and Calvin Johnson at San Diego State University.

With the funding, the researchers plan to use a quantum simulator to calculate the detector response to dark matter particles and neutrinos. The simulator to be used is an array of 121 neutral atom qubits currently being developed by Saffman’s group. Much of the research plan is to understand and mitigate the behavior of the neutral atom array so that high accuracy and precision calculations can be performed. The primary goal of this project is to apply lessons from the quantum information theory in high energy physics, while a secondary goal is to contribute to the development of quantum information theory itself.